The Style Series: Sasha Charnin

In 1977, at the age of 12, Sasha Charnin Morrison witnessed a sight that was to forever change the course of her life: the Vogue closet. “It was like a visual explosion,” she recalls. “At that moment, I realized, Whatever this is, I want to be a part of it.” With that, the born-and-bred New Yorker, who had dreamt of breaking out on Broadway, traded show business for the fashion industry — and playbills for mastheads.

Below, Charnin Morrison discusses her nearly four-decade magazine career working alongside the likes of former editors Grace Mirabella, Liz Tilberis, and her step-mother, Jade Hobson, and the lessons she’s learned along the way.

What’s your earliest fashion memory?

I wanted to be in show business and didn’t want to go to school anymore, so my parents found a one-on-one tutorial school on 59th Street for me. The genius of that was that the school was above Fiorucci when it first opened in New York. I mean, can you imagine? I would go to class, and then I’d go downstairs to Fiorucci every single day. I don’t even think my parents realized how incredibly impactful that was.

You’ve posted a number of Instagram photos of you and your mom wearing matching outfits. How did she influence your approach to fashion?

My mother, who is about to be 92, remains probably the most stylish person I know. She would dress us in similar outfits, so I was just this '70s hippie kid in black velvet smock dresses and Frye boots… The concept of thrifting and high-low really started with her for me. She and my father, who was, like, the greatest straight fashion-crazy shopper that I ever knew, were such influences on me in terms of being creative and stretching that dollar. We really didn’t have money to spend on luxury and all these things that she loved so much, like YSL, but we had vintage Vuitton luggage, which I still have. That monogram was all over the place.

At the end of the '70s, Jade Hobson, who was the creative director of Vogue at the time, became your stepmother…

How lucky was I? I’m 12-years old, and all I’m thinking about is being an orphan in Annie, and then my father separates from my mom and meets Jade Hobson. My first meeting with her — you know, meet-your-father’s-girlfriend day — was at the Vogue closet on Madison Avenue. I’ll never forget what I wore: a white thermal dress with shoulder pads by a brand called Parachute and Sacha London pink cone heel slingbacks. It sounds vile, but it was really of the moment — this was 1977. I walk in there, and it’s like, What is this? I just thought, Wow. Aside from meeting this statuesque, incredible woman, I’m introduced to this endless stream of belts and shoes and bags and couture and ready-to-wear moving in and out. It was like a visual explosion. At that moment, I was no longer interested in show business and just wanted everything that this was about. That was the mission. Then I went to NYU as a drama major and learned how to handle rejection and all of those things. I got my degree, handed it to my dad, and was like, Here you go. I’m going to Vogue.

Did Jade give you any advice that’s stayed with you?

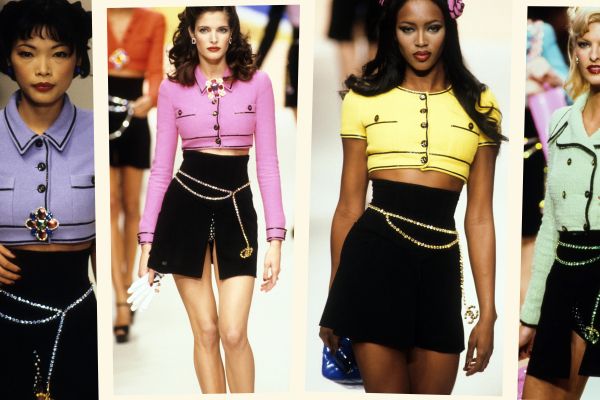

She was such a nice person in this vortex, but I think that’s one of the reasons why it worked so well for her. And she was mind-bogglingly talented. She brought this incredible sexiness to the table when she worked with [photographers] Helmut Newton and Steven Meisel and Denis Piel and Arthur Elgort and Irving Penn and Richard Avedon. Every time I go back and look at those pictures, I’m like, Wow, my dad was really lucky because these pictures are hot. The styling was insanely chic and gorgeous and dripping of something that you’d want to become. She was also the first editor at Vogue to style and photograph a lot of the Japanese designers in the magazine, in addition to being the first one to include Azzedine [Alaïa].

I would talk to her about [fashion] stuff and she got a kick out of my obsession, but she was more interested in gardening. She never gave me tips because she was just more in love with life and embracing that. Our relationship was just [about] actually having fun. This is a perfect example: in the '80s, I went to Bendels on 57th Street, where I’d bought my first Comme des Garçons, and saw this thing with clear sequins and graffiti-writing. It was Stephen Sprouse. I didn’t understand what was happening to me at that moment, but it was like a volcanic moment. So what was my Christmas gift that year? Five one-of-a-kind pieces made for me by Stephen Sprouse. I still have them, of course. She would do things for me like that, and it was just like, ‘Oh, I’ll call my friend Stephen.’ That was my life. It was crazy.

Between Jade and my father, I learned that fashion was a business, but I also learned about style and how to weed out the not-so-chic with the chic and then how to blend it all together, which came from my mom, too. With all the designers in the Village and the designers that didn’t have a phone, it was really important to have that balance.

You’ve worked with some incredible female fashion figures, like Grace Mirabella and Liz Tilberis. What did you learn from them?

Now that I think about it, I have been blessed in my career with the most incredible mentors. I suppose, without even thinking about it, that I not only aligned myself with people that would support my vision and be incredibly influential but I also aligned myself with the most incredible women.

My first big job was [in 1986] at Vanity Fair working for [creative style director] Maria Schiano, who was a legend. She was the right hand to so many different people: Calvin Klein, Armani, Yves Saint Laurent… I was so young — I was 21— and I didn’t understand anything about what was happening in terms of her incredible brain in fashion, but she was probably the most important person [in my career]. In nine months, she taught me everything about what not to do, and that’s so important; if your first experience is fluffy and happy and then the next experience is awful, you’re not prepared, especially in fashion. I was really treated like crap. I was that assistant. So I would say that my devil wore YSL because she basically fired me over a dog biscuit that I was delivering to Carolina Herrera for Christmas. Back then, if you did something wrong, you didn’t know if you were really fired, so we always went back because we loved it so much, even though it was torturous. But I finally knew when I got fired. If I’d played the game better, I’d probably be in Paris right now.

My second boss was [former Vogue editor-in-chief] Grace Mirabella at Mirabella, which was a startup. I was the first one to get there and the last to leave. It was grueling, but it was so much fun. If you raised your hand, they gave you the job. You don’t get a degree in fashion magazines; if you have the chutzpah, you say ‘I’ll do it,’ and then you become the swimwear editor or the model booker, which is what I did there. Grace gave me so many entrées into the world of high-fashion and actually wrote the foreword to my book [Secrets of Stylists: An Insider's Guide to Styling the Stars]. She was so interested in whatever it was that I had to say, even though I was not your typical editor — even at my thinnest, I wasn’t thin enough or I wasn’t this enough, like in show business. That’s also when I worked with Jade, who was the creative director. They were really supportive of things that were a little off and thinking about things outside of the box.

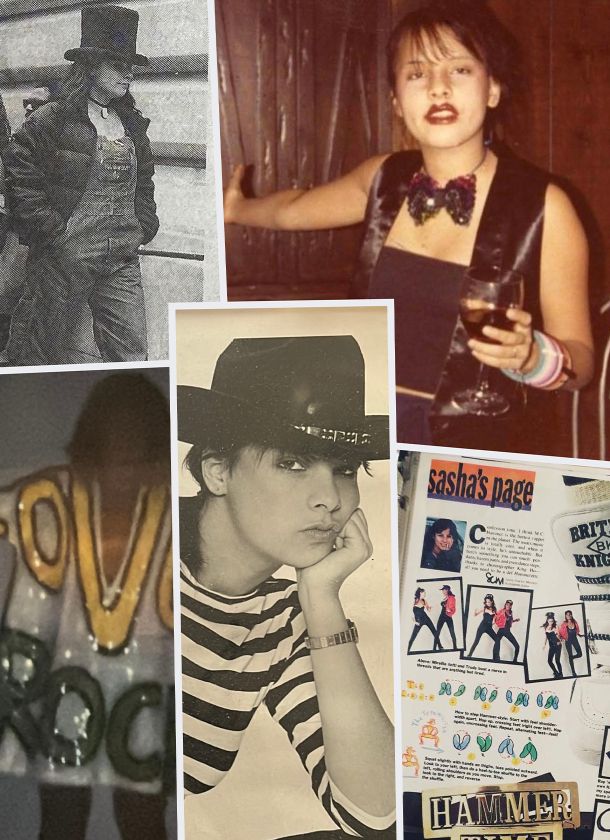

My next job was at Seventeen. Midge Richardson was a former nun, and she was the editor-in-chief. She and Nancy Hessel Weber, who was the creative director, gave me a voice with my name on a page. We couldn’t think of anything, so they just called it ‘Sasha’s Page.’ That was the place where I was able to understand the responsibility that we have to the reader: there may be certain things that you want to do, but, in the end, if it doesn’t benefit the reader, you have no business editorializing it. It was five years of bliss, but, at the end of the fifth year, I realized that I needed to move back into luxury.

At a Cartier event, I saw Lucy Wallace, who had been an assistant with me — her bags are now MZ Wallace — and she said, ‘I’m at Elle. Do you want to come to Elle?’ I wish it was that easy now. I went to Elle for four-and-a-half minutes because where I really wanted to be was Harper’s Bazaar. I had never seen anything like it from an editorial point-of-view. It was like, Whatever it takes I’ve got to get myself to Harper's Bazaar. In those days, if you took a job after you’d just accepted another job, you were known as a jumper, which was really bad for your reputation — that’s when things mattered. But I needed Elle to get me to Bazaar. Within a month, I got a phone call from Paul [Cavaco], who was one of the creative directors. I thought he was calling me for help for a prom dress for his daughter — I didn’t know what the hell was going on. He said, ‘The job that you have is open here. Do you want it?’ I just thought, Oh my god. And then: What am I gonna do? My reputation’s on the line. Should I give it more time? I was actually advised to stay by my advisory committee, but I made the decision to go to Bazaar because that job would not have been open again. I was about to get on the plane to go cover collections for Elle, so I had to resign over the phone, and then I went to Paris as the editor for Bazaar, confusing everybody.

At Bazaar, I got to work with the most incredible people, like Liz Tilberis. There are angels, and she was one of them on so many levels. She just giggled all the time. She taught us that you could love fashion and do your work but you also need to live your life and enjoy your life. It’s very difficult in business to understand that because you sacrifice to have these jobs… She had a trust in us that I’ve never experienced again. We were all there when she passed away. Then it was over, and we had to move on.

Do you think the editorial world still has these strong forces in it?

I believe there are wonderful people out there, but they are not given the tools that we had, so it’s just a different ball game. But the great thing about the business is that it’s built in a way that it needs to constantly evolve — that’s what made all of those places amazing.

I’m going to be very transparent about how I feel about Vogue right now: there’s an opportunity that’s being highly, highly overlooked and missed. Vogue will be there forever — it was there way before what we have now and it’ll be here way after — so what has to happen is that it has to evolve. It can’t just be about internet hits and impressions and likes. Anna Wintour has an opportunity to change the course of the way the business is for everyone because that’s the power that magazine has. And it’s so disappointing that that doesn’t happen. The point is that sometimes you need to say, I need to step aside and give this to someone who can do it. Now, they may be thinking, ‘There’s nobody out there,’ but maybe they’re not looking. I feel there are plenty of people out there who could make these changes. People are, like, physically and mentally anguished over the fact that nothing is happening. It’s like a moment in that movie Big: the toy has to change. Even if it doesn’t work, we’re in an era where you can do something that bombs, but then it becomes content. I always have hope that everything could change for the better. I don’t think it’s a lost cause.

I have nothing to lose in saying what everybody’s thinking because I have no brand telling me I can’t. It’s almost like, Am I the Joan Rivers [of the industry]? Yes, I would take that happily. I have a love for fashion, and I feel like it deserves more. The fact that the entire industry, for the most part, has been wiped out — with these incredible creative directors and fashion editors sitting around doing nothing — is mind-boggling to me.

Does fashion today still excite you?

“I still live and breathe it. I just absolutely cannot get enough of it. Even though I love to criticize it, I criticize it in a way that I think is funny and beneficial because I come with receipts — I actually know what I’m talking about. I feel like my place now is to take everything that I was quiet about — everything that I listened to and learned to reference — and not only resell it but also tell it. You know, this is my dress-and-tell era. I can say, I was there. I love the fact that it all can live on and constantly evolves. When people say fashion is dead, I always say, What are you talking about? I just ordered 15 things. It doesn’t end.

I cannot see a day without a package being downstairs — it’s frickin’ crazy — but I’m better about it now because I’m thrifting and looking at pieces from the past more than ever before. With the way that luxury runs itself, that craftsmanship and attention to detail doesn’t exist anymore. I’ve also been so priced out of the newer pieces — $10k coats are not things that I can afford — that it’s soured a lot of the experience, but that doesn’t mean that the designer I love doesn’t have something from another collection that I think about and can find. Because I have this knowledge, I can look at something and say, Oh my god, that Miuccia Prada coat is very similar to the coat from the 1999 Spring collection, and then go online to find it.

If I could buy every Miu Miu coat that has ever been or every Stella McCartney piece from the collections that she showed in London before she went to Chloé or every piece of Krizia that Alber Elbaz designed for the one season he was there or every Claude Montana piece from his two years at Lanvin, I would gladly do that rather than get new stuff because the design and workmanship is so covetable.

At ReSee, every one of our vintage pieces comes with a story. This is, in large part, thanks to our unmatched community of consignors.

Though parting with such sartorial treasures may not be easy, the exceptional personal care we put into ensuring that they will go on to live a second (or, sometimes even, a third, fourth, or fifth) life offers a thrill — one rivaled only by that of the besotted shopper who adds them to her wardrobe.

Sell with us